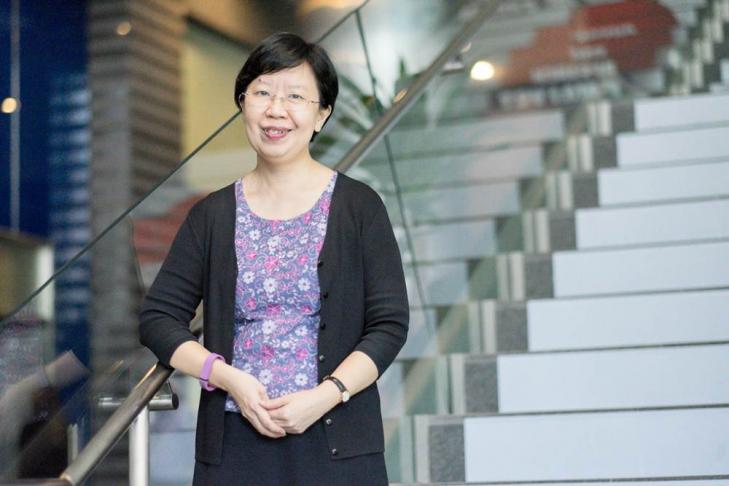

SMU Provost Lily Kong, widely regarded as one of the world’s leading social and cultural geographers, studies the complexities that surround a society’s religious spaces and practices.

Back to Research@SMU Issue 40

Photo Credit: Cyril Ng

By Shuzhen Sim

SMU Office of Research – In culturally diverse, relentlessly developing cities such as Singapore, tensions naturally arise over the use of space. Buildings with deep historical significance stand in the way of new developments; churches, mosques and temples sit cheek-by-jowl alongside secular public areas; green spaces and wildlife habitats are affected by pollution and environmental fragmentation. How can societies understand and negotiate such tensions, and perhaps find urban planning solutions that make cities more liveable for all?

Lily Kong, Provost and Lee Kong Chian Chair Professor of Social Sciences at the Singapore Management University (SMU), has built her career around exploring complex socio-spatial issues such as these. After 24 years as a researcher and top administrator at the National University of Singapore, Professor Kong joined SMU in September 2015, in a landmark appointment that saw her become Singapore’s first woman provost.

Religion, space, conflict

Professor Kong has a long-standing interest in religious spaces such as churches, mosques and temples. Tensions between religious groups, or between religious groups and secular society, inevitably arise over such spaces: in the US, for example, a proposal to build an Islamic community centre near the site of the 9/11 attacks in New York City caused an uproar; in parts of India, disputes between Hindus and Muslims regularly escalate into violence and loss of lives.

“When people firmly believe that a site is sacred, it’s not about rationality—it’s about belief systems, value systems, and emotional investment in the meaning of a space or place,” says Professor Kong. Yet, this sense of the sacred often runs up against modern urban planning principles. In cities such as Singapore, constant reinvention means that religious buildings may be demolished or relocated to make way for new developments.

Identifying the root causes of such tensions, and understanding how different societies have negotiated them, is critical for policy-making and urban planning, says Professor Kong, who explores these issues in her 2016 book Religion and Space—Competition, Conflict and Violence in the Contemporary World. “Policy-makers will begin to learn about how, in different societies, certain actions can in fact exacerbate opposition and violence, and how other ways of dealing with it might be ‘wearable’ for their own society,” she explains.

In Singapore, for example, the government has taken an even-handed approach to urban planning, with numbers of religious buildings in housing estates tied to the population size of each religious group. “That sort of even-handedness is a way of addressing any potential complaints about privileging a religion or discriminating against a religion,” says Professor Kong.

Where the sacred meets the secular

Outside of religious buildings, tensions may also occur over secular spaces—religious processions, for example, are highly visible events that often take place on public roads. While such occasions are deeply meaningful for the faithful, the rest of the community may in fact regard them—and their attendant noise levels and traffic disruptions—as a nuisance.

To study these issues, Professor Kong did some fieldwork of her own—she followed Thaipusam processions in Singapore, and interviewed kavadi carriers and their families about the ritual. Despite having to contend with temple officers shooing her off overhead bridges, this rewarded her with deeper insights into how devotees related to the procession and the regulations imposed on it.

For example, while the use of recorded religious music is permitted during the procession, participants felt that this was not the same as live musicians who can respond to the needs of the kavadi carriers—by playing more loudly or softly, for instance. In addition, they explained that it is difficult to carry the kavadi and then have to go to work—one of the reasons why the Hindu community has been pushing for Thaipusam to be made a public holiday.

In several cities, the authorities have banned religious processions altogether because of fears of violence. This may be warranted under certain circumstances, says Professor Kong. But before resorting to such drastic policies, a better understanding of both religious and secular concerns can help regulators ensure that the faithful are able to practice and derive meaning from their rituals, in ways that are tolerable, if not acceptable, to others in a diverse society.

Finding fresh inspiration at SMU

The move to SMU has put Professor Kong—physically—right in the middle of the city, and given her fresh inspiration for her work. With Singapore’s colonial heart abutting its finance and technology-oriented central business district, issues such as conservation of national heritage, public consultation in urban planning, and the integration of migrant populations constantly capture her trained geographer’s eye.

“Looking at the city every day reminds me that the study of the urban and urban phenomena is central to making cities much more liveable for humanity,” she says, gesturing at the view from her office window. “Being in the city has just completely rejuvenated my interest in the urban.”

As SMU Provost, Professor Kong oversees academic matters, which include research, teaching, and continuing education. Her goal, she says, is to create an environment that encourages SMU researchers to do both theoretically sophisticated work, as well as work that has profound real-world impact. “The two are not mutually exclusive, but to combine them can be very difficult,” she says. “The challenge that I would like all of us together as a community of scholars to rise up to is to be able to achieve both those peaks of excellence.”

Having the right incentives in place, she says, will be essential for achieving this. Too strong an emphasis on publishing in top academic journals may turn researchers away from work that has impact on the community, while too much of a focus on real-world applications will provide a disincentive for pushing theoretical boundaries. At the same time, recognising that people have different interests and strengths is also important. “It doesn’t have to be the same person who achieves both—it could be a portfolio approach.”

Setting the goalposts such that it is clear that both fundamental and applied research are laudable and will be supported by the university, says Professor Kong, will go a long way towards helping SMU become truly world-class.

Back to Research@SMU Issue 40